Biopsicología del amor

jueves 27 de mayo de 2010

Biopsicología del amor

O, por ser mas precisos—del enamoramiento, del deseo, del afecto, del emparejamiento y de la sexualidad.

Un texto de la página de Helen Fisher. Nos pasa la referencia Norman Holland.

Helen E. Fisher, PhD biological anthropologist, is a Research Professor in the Department of Anthropology at Rutgers University. She has written five books on the evolution and future of human sexuality, monogamy, adultery and divorce, gender differences in the brain, the chemistry of romantic love, and most recently, human personality types and why we fall in love with one person rather than another.

Fisher maintains that humans have evolved three core brain systems for mating and reproduction:

- Lust: the sex drive or libido

- Romantic attraction: romantic love

- Attachment: deep feelings of union with a long term partner.

"Love can start off with any of these three feelings," Fisher maintains. "Some people have sex first and then fall in love. Some fall head over heels in love, then climb into bed. Some feel deeply attached to someone they have known for months or years; then circumstances change, they fall madly in love and have sex." But the sex drive evolved to encourage you to seek a range of partners; romantic love evolved to enable you to focus your mating energy on just one at a time; and attachment evolved to enable you to feel deep union to this person long enough to rear your infants as a team.

But these brain systems can be tricky. Having sex, Fisher says, can drive up dopamine in the brain and push you over the threshold toward falling in love. And with orgasm, you experience a flood of oxytocin and vasopressin--giving you feelings of attachment. "Casual sex isn't always casual" Fisher reports, "it can trigger a host of powerful feelings." In fact, Fisher believes that men and women often engage in "hooking up" to unconsciously trigger these feelings of romance and attachment.

What happens when you fall in love? Fisher says it begins when someone takes on "special meaning." "The world has a new center," Fisher says, "then you focus on him or her. You beloved's car is different from every other car in the parking lot, for example. People can list what they don't like about their sweetheart, but they sweep these things aside and focus on what they adore. Intense energy, elation, mood swings, emotional dependence, separation anxiety, possessiveness, a pounding heart and craving are all central to this madness. But most important is obsessive thinking." As Fisher says, "Someone is camping in your head."

Fisher and her colleagues have put 49 people into a brain scanner (fMRI) to study the brain circuitry of romantic love: 17 had just fallen madly in love; 15 had just been dumped; 17 reported they were still in love after an average of 21 years of marriage. One of her central ideas is that romantic love is a drive stronger than the sex drive. As she says, "After all, if you causally ask someone to go to bed with you and they refuse, you don't slip into a depression, or commit suicide or homicide; but around the world people suffer terribly from rejection in love."

Fisher and her colleagues have put 49 people into a brain scanner (fMRI) to study the brain circuitry of romantic love: 17 had just fallen madly in love; 15 had just been dumped; 17 reported they were still in love after an average of 21 years of marriage. One of her central ideas is that romantic love is a drive stronger than the sex drive. As she says, "After all, if you causally ask someone to go to bed with you and they refuse, you don't slip into a depression, or commit suicide or homicide; but around the world people suffer terribly from rejection in love."

Fisher also maintains that taking serotonin-enhancing antidepressants (SSRIs) can potentially dampen feelings of romantic love and attachment, as well as the sex drive.

Fisher has looked at marriage and divorce in 58 societies, adultery in 42 cultures, patterns of monogamy and desertion in birds and mammals, and gender differences in the brain and behavior. In her newest work, she reports on four biologically-based personality types, and using data on 28,000 people collected on the dating site Chemistry.com, she explores who you are and why you are chemically drawn to some types more than others.

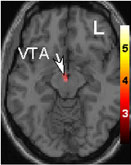

En este vídeo sobre "The Brain in Love" explica Fisher ese puntito clave en el centro del cerebro—en la parte más central, reptiliana y primitiva del cerebro. Así como otros sistemas cerebrales asociados con el amor:

Merecerían investigarse, por cierto, las conexiones entre esa actividad cerebral y otras asociadas a los sentimientos de suspense y narratividad—que también van ligados, nos dicen, a la segregación de dopamina.

Y aquí, una charla de Fisher sobre "The Science of Love and the Future of Women"

0 comentarios